It sounds like a belter of a riddle: name a part of the house that was treasured way, way, way more than it was actually used, a place verboten to many of those who lived there, a zone more cathedral to good taste and refinement than actual area to inhabit and enjoy. Welcome – or should that be welcome, but don’t you dare touch anything – to the ‘good room’.

For many Australians, this room was as much a part of growing up as the backyard or breakfast nook — the difference being that you were allowed to inhabit the last two.

Usually accessed via the first door off the passage as you entered a dwelling, the good room faced onto the front garden, and for many people, the view from the aspidistras was as close as you got. This is because the door to it usually remained firmly shut until a worthy occasion warranted its practically ceremonial opening.

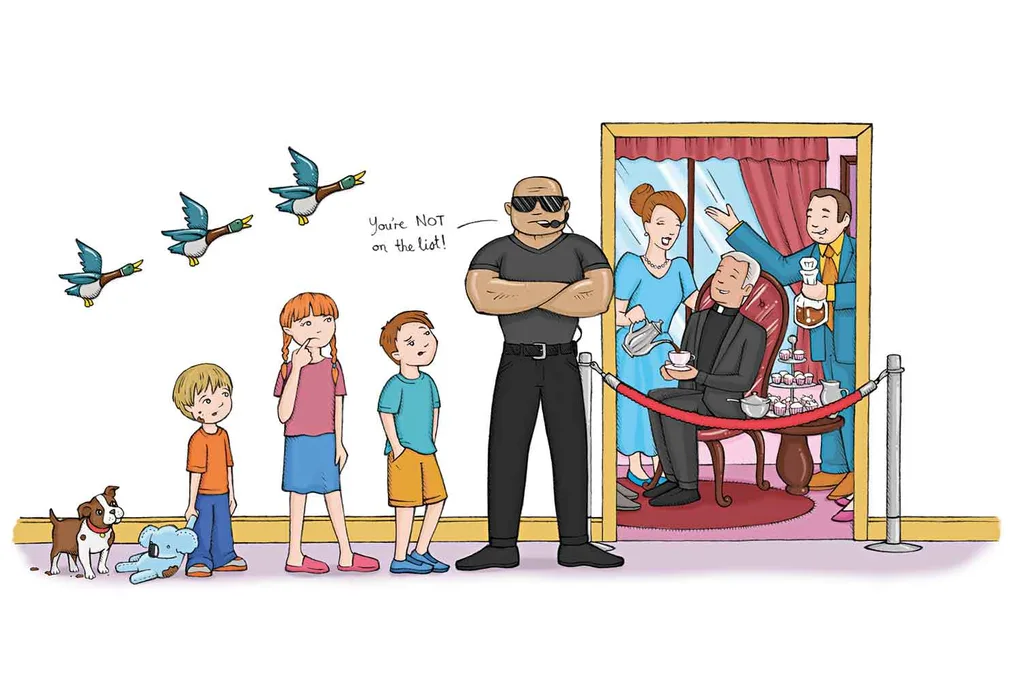

Children were admitted on the rarest of occasions with warnings beginning with the words “God help you if you…” As a result, you hung onto the room’s exterior door frame and positioned your body at a dangerous angle to snag a glimpse of the grown-up goings-on inside. Of course, anything so explicitly elicit took on an unmistakable lustre to young eyes. The good room might well have been called – to quote The Simpsons – “the forbidden closet of mystery”.

Only the most special guests warranted entry into the good room: the headmaster; the bank manager; the boss; your local MP; the neighbourhood priest/father/rabbi/lama; or relatives of enough years’ good standing. The point was to show this audience that one lived “nicely”. This was achieved on three fronts: formal etiquette, an array of sophisticated yet tasteful accoutrement, and overly polite conversation. If children were allowed over the threshold they were scrubbed, drilled and combed into the kind of docile submission guaranteed to make even the Osbournes look like the Von Trapps. In other words, smile, nod, bugger off and don’t smudge the surfaces.

Once inside, however, one was immediately struck by the fact that items that spent approximately 362 days of the year accumulating dust in the credenza were actually being used. We’re talking elegant snifters, brandy decanters with matching glasses, sterling-silver tea sets and even a container specially designed to hold sugar lumps.

There was also an unmistakable scent in the air… that of plastic. You see, the good stuff in the good room remained that way through the expansive use of clear, durable coverings. Metres of stiff, glossy material wrapped practically every fabric, from carpet and scatter cushions to lounge backs and settees (as they were called at the time). If one happened to be less than vigilant with the venetian schedule, the soaring temps of an Aussie summer resulted in an aroma that sat somewhere between recently refreshed rose potpourri – a good room staple – and an inner-city car mat factory.

Children were admitted on the rarest of occasions with warnings beginning with the words “God help you if you…”

Worse (or better, depending on the sophistication of one’s sense of humour), any human contact with these coverings led to friction, and friction led to certain noises at extreme odds with the rarefied atmosphere one was attempting to evoke in the good room, leading to the most delicious, giggle-inducing tension. Looking back now, it seems the plastic-covered Liberty prints, samovars and silverware might have been a tad contrived, a colonial decor hangover trying to prove we were something that never existed in the first place. Or perhaps we just outgrew them as Australians realised there was no reason that every room in our home couldn’t be the good room.

You might also like:

Retro classic: celebrating the beanbag

Throwback Thursday: Electric blankets

Annette O'Brien

Annette O'Brien